In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

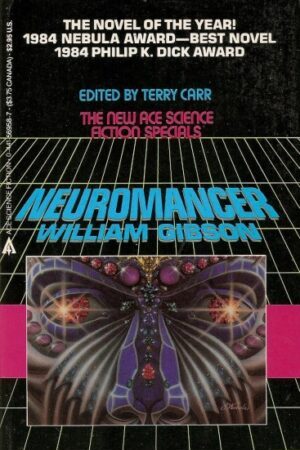

Today, I’m looking at a classic novel of the late 20th century, Neuromancer, took the science fiction world by storm almost immediately upon publication. The book brought terms like “cyberspace,” “matrix,” and “hackers” into the mainstream, and almost single-handedly launched the new subgenre of cyberpunk. Issued as a paperback, Neuromancer not only won the Philip K. Dick Award for best original paperback, but the prestigious Hugo and Nebula awards as well. It also gained attention outside the genre, becoming popular with a wide audience. I recently read that this year marks the 40th anniversary of the book’s publication, which in addition to making me feel old, made me wonder how the tale has held up over time.

Throughout the 20th century, the science fiction field went through periods of change. The earliest speculative stories gave way to the lurid adventures of the pulp magazines in the 1920s and 1930s, while the 1940s brought on a “Golden Age” where the authors began to pay more attention to the science, bringing greater rigor to their fantastic tales. Those authors were still dominating Analog magazine in the 1960s when I imprinted like a duckling on the square-jawed, plucky engineers who inhabited its pages. I remember hearing something about a “New Wave” when I was young, but other than encountering a few stories based on the softer sciences of psychology and sociology that avoided some of the standard tropes of the time, it didn’t have much impact on me. By the 1980s, however, I was reading a wider variety of stories and trying out new books. And in 1984, like many people, I ran across a novel that immediately attracted my attention: Neuromancer, by a new author named William Gibson.

Gibson was part of a group of writers like John Shirley, Bruce Sterling, Lewis Shiner, and Rudy Rucker, who wrote dark tales of a dystopian future where virtual worlds were becoming as important as the physical world. Their new style, which was dubbed “cyberpunk,” soon became a subgenre, attracting not only attention, but also imitators, not all of whom truly captured more than the surface feel of the original stories. And soon, just like political scandals after Watergate were branded with a name ending with “-gate,” new trends in science fiction began to be labelled with names like “steampunk,” “dieselpunk,” “raypunk,” and “atompunk.” Within a few decades, the new movement began to lose its focus, not because it lacked strength, but because its central ideas had thoroughly spread through the genre and become an inseparable part of science fiction.

About the Author

William Gibson (born 1948) is an American science fiction writer and one of the founders of the cyberpunk subgenre. A longtime reader of science fiction throughout his early life, he dreamed of becoming a writer. When he reached eighteen, Gibson traveled overseas, and ended up in Canada with an idea of avoiding the draft (although in his case, the draft notice never came). He met a Canadian woman, Deborah Jean Thompson, with whom he traveled to Europe, living on a shoestring, and garnering experiences that informed his later writing. The two married and settled in Vancouver, where he got a degree in English. Gibson began writing, and at a science fiction convention, met writer John Shirley, who encouraged his early career.

In his early stories, like “Burning Chrome” and “Johnny Mnemonic,” he began to experiment with the settings of cyberpunk, which reached full form in his first novel, Neuromancer. Two more novels set in the same “Sprawl” milieu followed, garnering him additional Hugo and Nebula nominations. He has not been a hugely prolific writer, producing just over a dozen novels, a number of short stories, and a few nonfiction works and essays. He now lives in the United States again, and his work continues to be well-received by fans and critics both within and beyond the science fiction genre. Gibson is a member of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame and was selected as a SFWA Grand Master in 2019.

Overtaken by Events

Neuromancer famously begins with the line, “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” The line is intended to evoke the formless gray static a television screen displays when it is not picking up a broadcast—but within a decade, to the many readers who would have their televisions hooked up to cables, the line evoked the image of a featureless black or bright blue screen. That example perfectly illustrates the difficulties a writer faces when attempting to predict the near future.

Yet, re-reading Neuromancer forty years later, I was surprised how well the story has held up over time. There are many things in the fictional world of the novel that have not yet come to pass. While urban areas have not reached the point of Gibson’s Sprawl, they continue to spread along the Eastern US coast. Computerized prosthetics have made huge progress, although they are still not linked directly to the nervous system. The world is linked in a web of data not too different from Gibson’s matrix, although it is not experienced through direct cybernetic links. While they do it through more primitive means, hackers already contend with representatives of governments and corporations in an effort to control data and systems. Governments could easily continue to weaken and international corporations strengthen as Gibson describes. And there is a small human presence in space, and increasing commercial access to orbit, so orbital habitats of considerable size are still certainly still a possibility.

The number of things Gibson missed, where the technology or events he described have been overtaken by actual capabilities, is much smaller than I had originally expected, especially since he created his cybernetic future world on a typewriter. He did not foresee the fall of the Soviet Union (although the 10th anniversary edition I read for this review seems to have substituted the word “Russian” for “Soviet” without adversely affecting the narrative). Like many authors, he missed the advent of cellular technology and miniaturization that put instant communication and access to the internet in everyone’s pocket. His description of the matrix, or cyberspace, is a bit more poetic than the current reality of the internet, but again, that might be realized in the future. And he did a great job of leaving things to the reader’s imagination, avoiding the excessive detail that would surely date the work over the passage of time.

All in all, there are few enough anachronisms in the text that even decades after it was written, I was very easily swept back into Gibson’s world of cyberspace cowboys in a decaying world.

Neuromancer

Case, an American expat in a seedy Japanese bar, is at the end of his rope. He is a former hacker, a cowboy with a custom cyberspace deck, whose employer caught him stealing and used a neurotoxin to strip him of his ability to access cyberspace. He has come to Chiba in a desperate attempt to find an illegal clinic that might restore his abilities. But as his hope ebbs, he is becoming more careless about his safety and what kind of jobs he takes, using more drugs and flirting with death. He has a girlfriend, Linda Lee, who steals from him and gets herself killed. The novel’s opening, in addition to evoking a dark future, conjures the feel of old noir detective novels, with flawed protagonists in situations they cannot control. Gibson writes beautifully, and the reader is immediately swept up in the story.

The novel’s plot kicks in when Case meets Molly, a mercenary with silver lenses implanted over her eye sockets and razor-sharp blades that emerge from under her fingernails. She takes him to meet Armitage, an enigmatic man who offers to restore Case’s nervous system in return for doing a job. He agrees, and soon they are off to the Sprawl, the urban blight that covers nearly the entirety of North America’s Eastern Seaboard. But his benefactors also make two other changes when they repair his nervous system: they put blockers in his organs that prevent him from doing drugs, and toxin sacs that will dissolve and kill him if he disobeys directions.

Case and Molly begin doing jobs for Armitage, breaking into secure cybersystems and gathering data. Case encounters a mysterious entity in cyberspace that calls itself Wintermute, which may be an artificial intelligence, or AI, and they begin to realize their efforts are repeatedly bringing them into contact with the multinational corporation Tessier-Ashpool S.A. Case encounters an old friend, Dixie, who is dead in the physical world, but still resides as a personality in cyberspace. Case and Molly try to find out more about Armitage, and what his goals are. Case discovers that Armitage is Colonel Corto, an American soldier who led a doomed mission against the Russians. Another member of their team is added, Peter Riviera, a sadistic man who can project images directly into other people’s brains.

The team takes a shuttle to Freeside, a gigantic orbital facility at one of Earth’s Lagrange points, a kind of Las Vegas in space. Case is sent on a side trip to the Zion cluster, a Rastafarian facility whose leaders are sympathetic to whatever mission Armitage is pursuing. The Rastafarians are a refreshing change from the other characters, lively, spiritual, and happy, and provide the team with one of their tugs for transportation. The team’s mission becomes clearer. There are two AIs controlled by Tessier-Ashpool that want to merge, which will violate the rules of the Turing organization, whose goal is to limit cybernetic intelligence. Armitage, who turns out to be an artificial personality overlaid over that of Colonel Corto, begins to unravel, and soon is gone.

Riviera betrays the team, and Case and Molly must infiltrate a Tessier-Ashpool orbital facility. There they find a nest of corruption and depravity, and have to fight not only to achieve their mission, but for their very lives. Artificial intelligences are at war with insane humans, with the future course of humanity hanging in the balance.

The tale comes to a conclusion that, while somewhat enigmatic, is much more hopeful than the story that preceded it. The book is immersive, compelling, exciting, and ultimately very fulfilling. It is easy to see why it is hailed as a classic of not only science fiction, but all of literature.

Final Thoughts

Neuromancer is a fantastic book, which not only established William Gibson’s reputation with his very first novel, but put the cyberpunk subgenre of science fiction on the map. Now that I’m done singing the book’s praises, I turn the floor over to you. What are your thoughts on Neuromancer, or Gibson’s other works? And what other books from the cyberpunk subgenre would you recommend to others?

I originally bounced hard off or Neuromancer when I first read it, despite loving Cyberpunk as a genre (my introduction to the ur-source went backward, started with Ghost in the Shell and the Cyberpunk 2020 RPG then walked backward to Gibson in a kind of reverse intellectual pilgrimage.) Then I read his short story collection, Burning Chrome and something clicked and when I re-read Neuromancer it just blossomed it something singular. The Tech, the Street . . . in Gibson’s stories it’s always this kind of third character driving a sort of obsessive love triangle with and in his protagonists. That unlocked some of the book for me, and watching Molly and Chase dance around each other and then get drawn back to the tech, the wires, always the wires, well it resonated differently (gods, the line “ITS THE WAY I’M WIRED, I GUESS” still echoes in my head from the second time I read it) . Like the plot was always solid and engaging, if a bit pants in spots – and to those like me who came to cyberpunk later it borders on the familiar – and I love Gibson’s prose but it took the short stories to underline the particular kind of damage his characters were working with and that made everything hit different on the second (and subsequent) reads.

I got to it late, in the early nineties. A page and a half in, I thought, “This is the book I’ve been wanting to read all my life.” It’s beautiful.

How many of us still see “snow” when we read that opening line about “tuned to a dead channel”, and not a beautiful blue (screen of death)?

As my “golden age” (aka 12-year-old) self got ambushed by the New Wave courtesy of Old Masters like Asimov (The Hugo Winners) and Pohl (“The Gold at the Starbow’s End”), I was prepped for cyberpunk’s appearance, especially its ethos of “The street finds its own uses for things”. I also liked the stories by their so-called “opposition”, the Humanists (Connie Willis, John Kessel, Kim Stan Robinson, et al.). A very fertile time for sf, the 1980s-90s.

Snow Crash was my first cyberpunk novel, and I still go back and listen to it now and again.

Bruce Sterling’s Islands in the Net is also a defining classic of the genre, and his tech is notably less fanciful; They use something that’s basically Google glasses to keep in touch virtually, there’s remote controlled drones that can be armed and have cameras, As best I recall, there’s nothing in there that doesn’t actually exist today except geopolitics. I could be wrong, it’s been a minute. It was futuristic as all get-out 35 years ago, though.

In a networked post-Cold War future, Laura and David (IIRC) are members of a democratic corporation (like but subtly different to a cooperative). They’re sent as representatives to a congregation of data havens to try to get them to maybe agree to some kind of international law. They get sucked into intrigue when Laura witnesses an assassination via drone, and winds up visiting a Rastafarian data haven in the Caribbean, Singapore, and various other places; I honestly forget which other bits are from that and which from his short stories.

I decided to give it a reread since it’s on my Everand subscription; I’d forgotten the scop (although again, nutritious food made from single-cell organisms grown in vats is possible, it’s just nobody actually wants it) and the tailored drugs, those turned out to be harder than anticipated

ETA: and next page they’re doing business by telex because faxes and video calls are expensive, wowee

That was a trip. I remember when cyberpunk didn’t sound optimistic in comparison to reality.

> As best I recall, there’s nothing in there that doesn’t actually exist today…

Don’t forget the ceramic machetes. “All tech is dangerous–even tech with no moving parts.”

That would be one moving part, according the USFS axe manual.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/delivering-mission/deliver/one-moving-part-forest-service-ax-manual

Ceramic blades certainly exist. Nobody makes a machete with them afaik, but there’s no fundamental reason you couldn’t. That said, I think the real ones aren’t quite so superior as the blades Sterling describes. Ultra-sharp blades are one of those ideas that was really popular in sci-fi in the 80s and 90s but turned out to not work that well for obe reason or another.

I wonder how it would bear up to a re-read. My copy’s around here somewhere – might dig it out. I read it when it first came out and I agree, it was a nice bit of future-building.

And soon, just like political scandals after Watergate were branded with a name ending with “-gate,” new trends in science fiction began to be labelled with names like “steampunk,” “dieselpunk,” “raypunk,” and “atompunk.””

That’s partially deliberate. The term Cyberpunk was coined because the genre was largely focused on advanced computing/networking, and heavily influenced by hacker culture of the time, which had a heavy overlap, ideological and otherwise, with punk as a political movement.

The term “Steampunk” was coined by Gibson and Bruce Sterling to describe their collaborative novel The Difference Engine, which was very specifically conceptualized as Cyberpunk but with Babbage Engines instead of digital computers, and a large focus on Luddites, labor organizing and other forebears of punk. By that time, Cyberpunk was well on the way to becoming an aesthetic and starting to lose the political elements, and computing was catching up fast. The steampunk became an aesthetic, and then all the other “-punks” stared to appear, referring to the/an aesthetic of a particular era.

The Foglios insist on the term Gaslamp Fantasy for their 19th century mad science setting, Girl Genius for largely this reason.

I remember reading “Johnny Mnemonic” when it first came out in Omni and thinking “Neat – someone’s applied a punk esthetic to near-future SF”. That was before I’d read anything else by Gibson, or even knew who he was.

Gibson has a very particular and original style to his writing. The lack of excessive detail, as mentioned, may help to keep the book contemporary, but it extends into plot continuity, more like ‘stream of consciousness’ and it can be hard to follow. Some paragraphs just make no sense at all. The overall sense of anarchic confusion is maintained. I suggest keeping study notes for the book at hand, or at least a glossary, as it would then be much more intelligible and enjoyable, or else read it again.

Reading your article encouraged me to take my dust-gathering copy of Neuromancer down from my bookshelf and read the Introduction and the first sentence of the novel before writing this blurb. Thank you for the clear and concise summary and review.

Like Ad.Solte, I remember bouncing off Neuromancer when it first came out, but I no longer remember why — maybe I just wasn’t in the mood for noir that day. I’m not sure how well it has aged, given that the more we learn about the human brain the less likely it seems it will ever be able to handle the linearity and raw speed of computers. There have been some interesting bits of news, such as a recent report that a computer could (with practice, IIRC) come close to printing out what someone was reading — by monitoring not the voice but an EEG — but the ideas of cyberpunk seem (from what little I read) to be farther and farther out of reach. Not that I’m entirely happy about that — I would love to be able to call down black ice on spam callers — but that’s what I see.

Eugene R: I certainly see snow — but I’m 71 and remember Washington DC when only 4 of the just-12 possible channels actually had signals in reach, so I’m primed for that opening line. It would be interesting so see how sharply getting that line maps to age.

I think the line would be blurry. In 1984, I would definitely be seeing static/”snow” (growing up with tuning knobs for VHF and UHF channels). In 2024, I have enough years of tech to maybe slip into the blue screen of death image. It would be an interesting survey, yes.

Not just science fiction; I remember when the authors of Swordspoint et al were referring to their work as “mannerpunk”. ISTM there was a period of 15-20 years when *punk meant “Look at this astounding new thing we’re doing!”

I don’t remember exactly when I first ready Neuromancer but I do remember a good friend of mine telling me quite insistently that I had to read it. I did, and I was hooked. For the next few years, I couldn’t get enough cyberpunk, But, because I read a borrowed copy, I didn’t have it in my collection. So it was a long time before I re-read it.

I did so a few years ago and was struck more by the punkness of it than the cyberness, if that makes any sense. Gibson’s writing is always a bit raw and impressionistic, but this one has an almost kinetic impact that still lands for me. It still feels quite fresh to me partly because it isn’t trying to fit into an established subgenre: it’s just rolling along on its own energy.

That was an excellent summary. Much, much easier to understand than the book itself :)

I always find I enjoy Gibson more for the vibes than the actual plots.